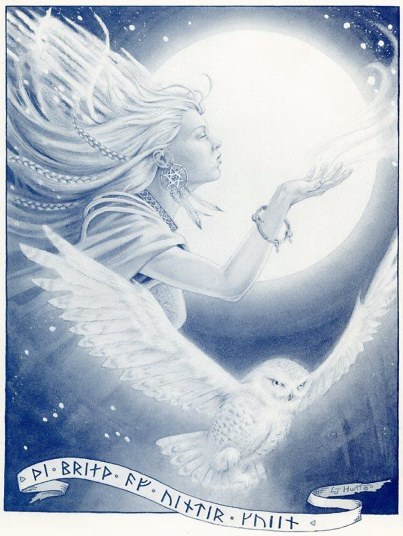

The Winter Goddess

The Winter solstice approaches. In the frigid night sky, the stars of 'Friggs's spindle' turn in the same place where we see the constellation of Orion. Outside our brightly lit homes, the darkness grows.

The longest time of Darkness in the year is called "Night of the Mother", as the Goddess labors to birth Light back into the world. At Winter solstice, the sun dies. Time stops. Then as Freya spins the wheel of fate once again, "Jul" in Norse, the sun is reborn. Her hand holds the spindle, a symbol of women's wisdom and skill. From her basket, she plucks a handful of wool, freshly combed but still unformed. Placing it on her wheel, she makes the ancient sure-handed gestures of the spinners, pulling the wool, winding it about the distaff, working it to a smooth and useful shape. So doing, she reminds us of her presence in the cycle of death and rebirth.

Freya was also called Froya and Frigga in Scandinavian countries, Holda in Germany and Modir in Russia. She was a Goddess of the Winter and her sacred goose brings to mind both protection and soft, snowy white down. When snowflakes fell, she was "shaking out her bedding".

As Freya she was sister-lover-mother to the God Frey, god of Yule. As Frigga, she gave birth to Baldur, the Norse God of the Sun. Throughout Northern Europe, she has been worshiped as the multi-faceted goddess of birth, death, sex, the underworld, the earth, the stars; a goddess of magic, the Great Sow wed to the Boar, the Mistress of Cats, the leader of the Valkries. As Saga, she inspired divine poetry and as a Spinner of Fate, she was associated to the Norns.

Just as Freya-Frigga was connected most closely to birth, sex, and motherhood, her Dark Twin was known as Skadi, the "Destroyer". In the celebration of Yule we can see elements of the triple goddess Freya-Frigga-Skadi and the spinning wheel of death-birth-life.

Most widely known is the story of Freya (or Frigga), her son Baldur and the Mistletoe. Seeing it was his fate to die, she went out into the world and asked that all things promise not to harm her son. She overlooked the insignificant mistletoe, and Baldur the Sun was killed by a tiny dart of this symbol of re-birth and Winter solstice. White berries formed as Freya's tears fell among the evergreen leaves.

The plant was sacred to the Druids, who saw that as the oak lost it's leaves, the mistletoe remained ever green, thus catching up the soul of the tree and holding it for the Winter. Mistletoe was also valued as an aphrodisiac and was linked to both Freya as a sexual Feminine and to the sexual Masculine.

The white berries were seen as the sperm of the gods and linked to fertility and prosperity. Rituals after the new moon of the Winter solstice involved the cutting of the plant with a golden sickle by a Druid priest. Pieces of plants were then distributed to the people for good luck in the coming year. Similarly, when the Winter Goddess is seen in her aspect of Skadi, there was a ritual emasculation of the Sun, and the lap of the goddess was bathed in the genital blood of the god Loki (Luck). If Skadi was pleased, the Sun would be reborn and Spring would return.

In her death aspect, Freya was the Great Sow; her consort the Boar was sacrificed; the head decorated with fragrant herbs and served at the Yule feasts.

In the dark we are at our most intuitive, most open to the path we will set before us for the coming year. At Winter solstice, Freya plucks us up like a clump of soft wool, our rough shaped selves ready to experience something new. Now is the time to clean ourselves up, pull out the useless straw, to pluck out the last bits of what we let go of at Samhain and are finally ready to let die with the old year. Freya turns her wheel, spinning with us. We prepare to begin spinning the creation of our own New Year, planning the re-birth of our selves, seeking the new, getting ready for changes, inviting possibility. During this longest night when the Old Year is dying, we look towards the light of midsummer and to our New Year at it's full bloom.

Blessings

Leigh Barrett

Sources:

Walker, Barbara G; The Woman's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets.1983. Harper Collins Pub. P 112, 324-325, 660-661, 666, 941-942, 956,

http://www.goddessgift.com/goddess-myths

http://www.thorshof.org/frigg.htm

Cernunnos

Cernunnos in Celtic polytheism is the deified spirit of horned male animals, especially of stags, a nature god associated with produce and fertility. As a "Horned God", Cernunnos was one of a number of similar deities found in many ancient cultures.

Cernunnos is known, from archaeological sources such as inscriptions and depictions, to have been worshipped in Gaul, Northern Italy (Gallia Cisalpina) and the southern coast of Britain. The earliest known probable depiction of Cernunnos was found at Val Camonica in Italy, dating from the 4th century BC, while the best known depiction is on the famous Gundestrup cauldron found on Jutland, dating to the 1st century BC. The Cauldron was likely to have been stolen by the Germanic Cimbri tribe or another tribe that inhabited Jutland as it is quite cleary from south east Europe (See the external link below).

In Gallo-Roman religion, his name is known from the "Pillar of the Boatmen" (Pilier des nautes), a monument now displayed in the Musée National du Moyen Age in Paris. It was constructed by Gaulish sailors in the early first century CE, from the inscription (CIL XIII number 03026) probably in the year 14, on the accession of the emperor Tiberius Claudius Nero. It was found in 1710 in the foundations of the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris on the site of Lutetia, the civitas capital of the Celtic Parisii tribe. It depicts Cernunnos and other Celtic deities alongside Roman divinities such as Jupiter, Vulcan, Castor, and Pollux.

The depictions of Cernunnos are strikingly consistent throughout the Celtic world. His most distinctive attribute are his stag's horns, and he is usually portrayed as a mature man with long hair and a beard. He wears a torc, an ornate neck-ring used by the Celts to denote nobility. He often carries other torcs in his hands or hanging from his horns, as well as a purse filled with coins. He is usually portrayed seated and cross-legged, in a position which some have interpreted as meditative or shamanic, although it may only reflect the fact that the Celts squatted on the ground when hunting.

In Wicca, imagery derived from historical Celtic culture is sometimes used, including a depiction of Cernunnos, often referred to as The Horned God. This version of Cernunnos is based little on historical findings and more on phallic symbolism, merged from elements of Pan. The adherents generally follow a life-fertility-death cycle for Cernunnos, though his death is now usually set at Samhain, the Gaelic New Year Festival usually taking place on October 31. It should be noted, however, that Wicca is in no way an exact reconstruction of historical Celtic religion and culture, despite claims by some Wiccans.